Harry Easterling was getting impatient.

It was the end of his midnight shift, and he had an appointment scheduled before he could head home. That wouldn’t have been a problem, but Easterling carpooled to work and his co-rider was late.

It’s the car-pooler’s dilemma: Everything works great until you’ve got to be somewhere on time.

Easterling stood near the time clock at his rural Ohio job and waited.

On the whole, he was a patient guy, but no one likes to miss appointments. He’d planned to check out a house for sale in a nearby township and hated the thought of the real estate agent sitting there, annoyed, twiddling her thumbs.

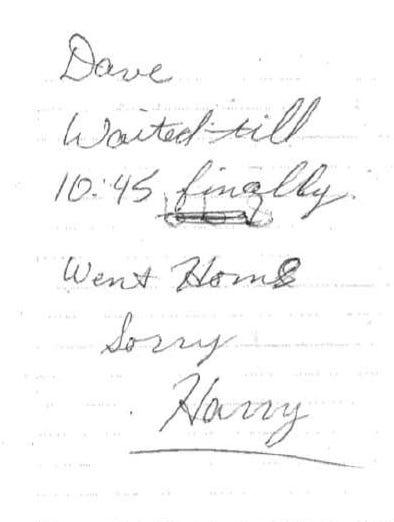

So Easterling made a plan: He’d leave his car pool buddy a note, run to the appointment, then come back to get his friend David Bocks, who surely would surface by then. He scrawled a missive:

Dave: I’ll be back after I go look at the house in Ross. – Harry

Harry Easterling was a fellow Fernald worker and David Bocks’ carpool buddy. When David didn’t show up after their shift ended, Harry left him a note.

Harry Easterling was a fellow Fernald worker and David Bocks’ carpool buddy. When David didn’t show up after their shift ended, Harry left him a note.

Provided; UNSOLVED MYSTERIES

When Easterling returned, his note appeared untouched. This was getting weird.

“Have you seen David?” he asked the receptionist.

The reply was perplexing: Nope, haven’t seen him.

Easterling waited some more, then scratched out his first note and wrote a new one:

Dave: Waited till 10:45, finally went home, sorry. – Harry

Easterling went home. As odd as the situation felt, he wasn’t worried. The place that employed Easterling and Bocks was a sprawling, 1,050-acre site, and the two worked the graveyard shift. David was probably immersed in a fix-it project somewhere and lost track of the time, Easterling figured.

The truth, he would soon learn, was more bizarre and gruesome than anything he could have imagined.

Driving through the stretches of green fields in rural Ohio, the sudden emergence of an ugly cluster of industrial factories was jarring.

This was farmland – acre after acre of corn and soybeans and wheat and oats. The houses nearby would be politely described in real-estate listings as “rustic.”

Michael Snyder, Enquirer Archives

But the people who lived here liked it that way. They liked space between themselves and their neighbors. They liked their kids coming home with mud-covered knees. They liked that they could buy their milk from a dairy farm right down the street.

They even liked those smoke-spewing factory buildings that jutted up from the landscape.

It was a huge complex and it could look a bit foreboding to outsiders, what with the security fencing and barbed wire and armed guards.

A lot of the neighbors didn’t know much about the plant. They saw the red-and-white checkerboard pattern adorning a water tower that loomed over the property and equated it with the nearly identical logo for Purina, a pet food brand. That the complex name was the Fernald Feed Materials Productions Center, and their impressions were solidified.

And why not? Wasn’t rural Ohio the perfect place to make dog chow?

A few residents surely remembered the headlines from the 1950s when the plant was built, but those headlines had been vaguely about atomic power and fighting Russians. Those who did remember seemed to take pride in the notion that their biggest employer was key to protecting the country.

Besides, there’s a lot of leeway given to big employers. Some 1,000 people worked at that plant, and it was known to pay well. Families depended on it. It provided them with food and braces and college educations. It allowed women to choose to stay home and raise families rather than work. The two-income households in the area weren’t just comfortable; they were well off.

Whatever that plant produced, the locals were grateful it was there.

Provided

David Bocks was a quiet man who wore thick glasses. When he was a child, he’d gotten sick – family lore pointed to measles as the culprit – leaving him legally blind in his right eye. It kept him from serving in Vietnam.

He’d been born in Staten Island, New York, in 1944 to devout Catholic parents Anne and Russell Bocks. He was the middle of three children, all boys.

When the kids were still young, the Bocks moved from New York to Ohio, where all but one brother would stay until their deaths.

In high school, David had a Buddy Holly look about him – a bit nerdy with horn-rimmed glasses. He wore his hair cropped short in a military-style buzz, making his protruding ears especially noticeable.

By the time he was 20, he’d met and fallen in love with a petite and pretty brunette named Carline Noggler. When the two married soon after, they looked more like awkward kids playing dress-up than adults starting a life together. A carnation pinned to his suit, David beamed in photos next to his lace and tulle-adorned bride.

Like David’s parents, the couple had three children. Tony was the oldest, born in 1966. Casey came next in 1968. Last came Matt three years later.

David wasn’t much for book smarts, but he liked to work with his hands. Cincinnati was always a great place for work like that. The port city on the border of Ohio and Kentucky was home to dozens of internationally known companies like Procter & Gamble, Formica Laminates, the Cincinnati Type Foundry.

Amanda Rossmann, The Enquirer

For a while, David worked at the Cincinnati Industrial Machinery Co., a manufacturing company that made solutions for cleaning and coating applications. In 1981, he was hired on as a pipefitter at Fernald.

His job was physically taxing, but straightforward enough. He was responsible for installing and maintaining pipe systems within the plant. The factories were 30 years old by the time he was hired, so pipes were cracked and leaking. Upkeep needs were constant.

The work suited David, who stood about 6-foot-1 and weighed between 180 and 200 pounds, depending on if you believed his bosses or his children. His son Tony remembers his dad as stocky with massive upper body strength and broad shoulders, no doubt an asset in a trade that required a lot of equipment lifting, hammering and tightening.

David took his job seriously. Far more was at stake than a tainted batch of dog food. As David and his coworkers well knew, the “feed” in Fernald’s title referenced the refining of weapons-grade uranium, one crucial step in the government’s creation of nuclear weapons.

The Mysterious Disappearance of David Bocks

In 1984, a father of three disappeared while working at a mysterious Cincinnati plant. It turned out he’d met a gruesome fate. What happened to David Bocks?

Amanda Rossmann, arossmann@enquirer.com

Fernald was a uranium processing plant. Uranium is used in bomb-making because it’s fissionable – meaning it can be split in two and release the kind of energy that nuclear bombs need to go boom.

When David applied at the plant, Republican Ronald Reagan had just walloped Democrat and incumbent President Jimmy Carter in a 489-49 Electoral College win. Reagan had been critical of the U.S. stance on arms control and promised to win the nuclear race that was underway with the Soviet Union.

The new president helped ignite a wave of patriotism that fueled movies like “Rambo” and “Top Gun.” He also breathed new life into the nuclear industrial complex, causing a brief spike in hirings at plants like Fernald.

David, for one, made good money there, where he worked from midnight to 8 a.m. The biggest downside to the job was its location, some 30 miles west of his home in Loveland. He soon remedied that by carpooling with coworker Easterling.

The only thing vaguely amiss when the two men met up before the start of their June 20, 1984, shift was that David had missed a workday the prior week because his car had broken down. There was nothing to indicate this shift would be his last.

While Easterling was wondering where his car pool buddy had gone, Fernald employee David Allen had arrived for his morning shift in Plant 6. His job was to ready a gnarly hunk of equipment called a NUSAL Vat.

The vat was about 4 feet wide and more than 10 feet long. It was filled with a slurry of sodium chloride and potassium chloride kept at a sweltering 1,350 degrees Fahrenheit.

Provided

The slurry’s job was to shape and mold chunks of uranium called ingots. Typically, a heavy concrete lid more than 3 inches thick covered the vat unless it was in use. Even when not in use, a small opening remained, measuring 22¼ by 9 inches – essentially the size of two sheets of notebook paper taped together length-wise.

That opening was largely useless, save for employees playfully tossing in apple cores and watermelon rind to watch the fruit explode in the lava-like temperature. To either add salt to the slurry or to drop in the ingots, a hefty hoist had to lift off the hefty lid.

Bill Welch was usually the first worker to check the vat and start readying it for production. He peeked into the vat and noticed that the slurry inside looked odd. It was covered in a sooty crust that he’d never seen before. He spotted some odd, light-colored flotsam in the mix, too, but thought his eyes were playing tricks on him. Soon, coworker David Allen lifted the lid off the vat, saw much the same and likewise shrugged it off.

It wasn’t until later that day, when a proper search was underway for a missing employee, that Welch and Allen realized their earlier discovery was more than odd. It was what remained of David Bocks.

Casey Bocks and her younger brother Matt had spent the weekend with their father. Tony, at age 17, was living on his own and married, so he tended to grab dinners and short visits with his dad rather than doing overnight stays.

Casey said that last weekend with her father was completely ordinary.

“We just hung out,” she said. “I mean, usually, we would go and eat someplace and then just hang around the house. It wasn’t anything extravagant. We never really did a whole lot of anything.”

Provided

David bought groceries and stocked the fridge. A chain smoker, he slapped three packs of cigarettes on the kitchen table. He worried sometimes about being too sleepy on the job, so he took the kids home a little early to allow for a nap before his midnight shift.

Looking back, Casey recalls nothing that stood out about the visit. There certainly had been no meaningful heart-to-hearts or unusual expressions of fatherly love. In fact, it was the opposite: David talked with Casey and Matt about some housekeeping matters as they planned an upcoming trip to Florida.

The next day, her mom’s boyfriend took Casey and Matt to Churchill Downs, the racetrack that serves as home to the Kentucky Derby. The track’s in Louisville, about a 90-minute drive from Cincinnati. Carline had stayed home.

As the trio walked around, Casey swore she heard someone over the loudspeaker paging her mom’s boyfriend. She told him so, but he didn’t believe her. Who would be paging him, anyway? So they stayed until all the races were over for the day and headed back home.

Carline was waiting for them. Casey doesn’t know how her mom was told or by whom, but word had reached her that David hadn’t come home from his work shift.

“At that point in time, he was just missing,” Casey said. “We didn’t know what had happened.”

The story relayed was so bizarre, Casey couldn’t wrap her brain around it. How could someone go to work and simply disappear?

The Fernald plant straddled two Ohio counties: Butler and Hamilton. When the call came in about a missing person, it was routed to the sheriff’s office in the latter county.

Investigators first heard from Lawrence “Larry” Devir, a police officer who worked security at the plant, who told them a worker had gone missing. The second call came from a lawyer within Fernald’s legal department, according to handwritten notes within the department’s 351-page investigative file.

Michael Snyder, Enquirer Archives

Once investigators learned of the mysterious black sludge in the NUSAL vat, they ordered it to be cooled and drained. On June 23 – three full days after David disappeared – investigators were lowered into the furnace, where they inspected hardened slag measuring between 2 and 4 inches thick.

Officers used chisels to break up the slag, then an air hammer to remove the chunks from the oven floor. As they carved and chipped away at the material, they amassed a list of unsettling finds: Pieces of a walkie-talkie radio. Wire from a pair of safety glasses. An alligator clip from a nametag. Steel toes and eyelets from work shoes. All were items with a higher melting point than, say, a human body.

When investigators uncovered a ring of keys, Chief Deputy Sheriff Victor Carrelli lugged them to David’s toolbox, which he kept near his locker where he stored his street clothes. Carrelli fished out a padlock and tried the keys. Sure enough, one fit.

And, lest anyone think that maybe David’s belongings landed in the vat but not David himself, investigators chronicled one more disturbing discovery: multiple chunks of fragmented bone.

Hamilton County Sheriff’s Detective Pete Alderucci was among the main investigators assigned to find David Bocks. He answered to Carrelli, second in command under Sheriff Lincoln Stokes.

Carrelli, who died in 2007, had worked as an FBI agent for nearly 30 years before Stokes – a fellow FBI alumnus – announced in 1977 that Carrelli “can walk on water” and appointed him his second-in-command.

Provided

Alderucci was plenty experienced in grisly cases. When a big homicide case hit the department, he was inevitably the guy sent out first to gather evidence. But those cases, while disturbing, were always more typical fare – shootings, stabbings, strangulations. The Bocks investigation was something entirely different.

The thick investigative file bears this out. In it is page after page of instructions explaining the dangers of handling each bit of debris pulled from the vat. After all, hunks of radioactive uranium had been lowered into that slurry again and again. Everything inside had to be surveyed for radiation before leaving the plant.

These tests were a far cry from those Alderucci usually saw in his investigations. These ones measured things like Beta + Gamma Exposure, Gamma-only Exposure and Alpha Contamination – and used instruments he’d never heard of – “pancake G-M with paper ‘alpha filter’” was one; Alpha Scintillation Survey Meter was another.

The results varied slightly, but the bottom line was that investigators were instructed to be careful with the evidence in a way they’d never encountered in another case, not for fear of contaminating the evidence, but for fear the evidence would contaminate them.

Peter Alderucci was the lead detective from the Hamilton County Sheriff’s Office on the David Bocks case, where bone fragments were found in a salt vat at the Fernald Feed Materials Production Center. This archived photo of Alderucci was taken in 1993 when he was featured in an Enquirer story about a new computerized finger printing system.

Fred Straub

They couldn’t eat, drink or smoke while holding the samples, and they were ordered to wash their hands after each handling. If the samples had to be cut or crushed, investigators were told to wear a fume hood or “an air-purifying respirator with a radionuclide filter cartridge.”

Even with these precautions, some of the evidence bore extra warnings: “Each individual should limit actual hands-on handling on sample to 13 hours of actual contact,” read several.

That’s because uranium is no joke. It’s a high-density metal found in rocks that kicks off ridiculous amounts of energy. Its slow radioactive decay is where most of the Earth’s heat comes from.

Uranium’s naturally occurring in small amounts, but to get the quantity needed for nuclear weapons, it has to be refined and enriched. When that’s done, it makes a powerful nuclear fuel.

Fernald had just one customer for the uranium it processed: the U.S. government. The plant itself was run by a private company called National Lead of Ohio that everybody referred to as NLO. That company, in turn, was contracted by the Department of Energy.

Fernald’s workers had to agree they wouldn’t talk about the top-secret nature of their jobs – not even to their own families. One employee, John Sadler, remembered: “You had to sign an agreement you wouldn’t talk about anything that you did there under penalty. I think it was $10,000 and five years in prison.”

Provided

Ice melts at 32 degrees Fahrenheit. Chocolate, at 90 degrees. When it hits 130 degrees outside, a human’s likely to get heatstroke.

The NUSAL vat was kept at a constant 1,350 degrees. It rarely varied by more than a degree, but when it did – say, by the lid being lifted and uranium ingots lowered in to be reshaped – electrodes immersed inside the vat kicked on to heat the slurry back to 1,350.

The vat stood about 4 feet tall in the middle of a grime-and-rust covered factory floor. On one end of the vat – the same end as the small opening – was a ladder that served as the only means of reaching the vat’s top, though there rarely was reason to do so. There was no plausible way for a worker to accidentally fall into the vat.

When the lid was removed to make room for ingots, it was lifted by a hoist that attached to a hook atop the lid. The hoist followed a prescribed path to move the lid aside without setting it down.

Harry Easterling, David’s car pool buddy, remembered the vat well: “It just looked like hell,” he said. “If you were to look down at hell and there was a big hole in the ground, that’s what it looked like – a big, open, red hole in the ground. Like a volcano.”

The slurry was so hot it literally glowed red.

Alderucci arrived before the vat was cooled. He remembers being struck by how hot it was to even stand near.

“You couldn’t get within 10 feet of it,” he said. “It’d be so hot it would – you would just burn to death.”

It just looked like hell. If you were to look down at hell and there was a big hole in the ground, that’s what it looked like — a big, open, red hole in the ground. Like a volcano.

Longtime employees dispute this memory. It was hot, yes, they said, but not unbearable. Easterling likened it to a sauna – uncomfortable, but certainly not fatal.

Alderucci remembers differently, and his impression swayed his theory in David’s death. Because it wouldn’t have been possible for David to accidentally fall into the vat, that left two possibilities: that David was put there by someone else or that he chose to enter the vat to end his life.

“Nobody could have killed him, carried him up,” Alderucci said. “What we determined was that he wanted to commit suicide. He had to get back, run up those steps and either jump or dive in that small opening.”

Despite Bocks’ size, he explained, it was a simple matter of process of elimination. Homicide was never considered.

“We had no reason to,” he said. “There was no indication, no evidence to show of any homicide.”

Anything radioactive is dangerous, of course, but processing uranium is also an exacting job.

That slurry had to stay a constant 1,350 degrees Fahrenheit, so its temperature was regularly monitored and anomalies investigated.

In the early morning hours of David’s disappearance, there was a dramatic anomaly.

The temperature in the vat dipped twice in a 15-minute span. The first dip, recorded at 5:10 a.m., was 28 degrees, lowering the slurry temp to 1,322 degrees. The temperature recovered slightly before dipping again to 1,324 degrees. After that, it crept back to normal and stayed put.

Provided

To make matters more complicated, engineer Robert Spenceley told investigators that the time printed on the temperature readouts was about 10 minutes fast, so the double-dip likely began closer to 5 a.m.

Spenceley did some back-of-the-napkin math: You need 980 BTUs of heat to boil a pound of water, and the human body consists of about 90% water. If David weighed 180 pounds like investigators thought, that would likely cause a 25- to 30-degree temperature drop.

Problem was, no one had ever fallen into the vat before, so workers could only theorize how the slurry would react to a human body entering it. As disturbing as the thought was, they also didn’t know what trauma that body would endure. They only had their fruit tosses to go by, and when they tossed apples or watermelons – rind and all – into that slurry, the fruit exploded with a bang as loud as gunfire.

Human bodies aren’t quite the same as apples, however. It’s tough to find an analogous scenario on which you can base an educated answer. Volcanologist Adam Kent, a professor at Oregon State University, said he suspects the slurry would have behaved similarly to lava.

He pointed to a video online showing a couple of people tossing “organic waste” into a rumbling volcano. Viewers hear a loud pop, then see a series of violent explosions, one after the other, until the bagged items sink beneath the surface.

Kent suspects a human body would elicit the same reaction. The reason comes down to pressure: The extraordinary heat of the slurry would cause all liquids in the human body to rapidly evaporate, turning into steam. The steam pushes against its encasement – which, in this situation, would be human skin.

“Basically, the pressure becomes so much that the water can’t be trapped anymore and it explodes,” Kent said.

Without a proper experiment, this is just a theory, but it’s one even NLO scientists suspected back in 1984. An internal letter from an in-house scientist named H.E. Fairman includes the line: “The violent expulsion of the salt due to the introduction of water would also have resulted in several limbs or fracture bones being ejected from the furnace.”

Provided

But if David’s body exploded on immersion, how could he have ensured his entire body made it through the small opening? Why were there no limbs or bones found outside of the vat?

And why were there two distinct drops in the temperature readout?

David’s children think he was perhaps killed outside of the vat, then cut in two pieces and immersed in halves. Even if David had been suicidal, they say, he never would have chosen such a hellish way to do it.

Alderucci said families left behind by suicide often can’t accept the ruling. It’s too heartbreaking and guilt-inducing.

“I have investigated a lot of suicides, and people do it in very illogical ways,” he said. “Even people that know better – doctors, you know, people like that.”

Plus, he said his theory was bolstered by something else: “He was despondent. We knew that he was having psychological problems.”

It’d been a rocky few years for David Bocks. After he’d married Carline, things on the whole had gone like marriages are supposed to. The couple had three children, David had a steady job, everything was solid.

But then David started drinking. He wasn’t a mean drunk or a dangerous drunk, but he was a drunk nonetheless. It caused strife in his marriage. Carline tolerated it until she couldn’t anymore. Then she asked for a divorce.

David hadn’t wanted to split. He, like most married people, wanted a lifelong union – one much like his parents’. He tried to talk Carline into staying, promising things would get better, but the damage had been irreparable. She still loved him, she said, but it was time to move on.

So while David hadn’t been able to enjoy a picture-perfect marriage, he got as close to a picture-perfect divorce as he could. He and Carline didn’t fight, didn’t get nasty. He saw the kids regularly, he moved in with his parents and he sobered up, too.

To get sober, he stopped cold turkey. That sent him into detox, which, his adult kids now say, caused hallucinations. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, David was hospitalized three times, each stint shorter than the one before it – including a monthlong stay around the same time both of his parents died.

Provided

What precisely was wrong with David is, of course, tough to determine 35 years later. He worked with a psychiatrist who, in 1976, diagnosed David with schizophrenia and suggested his drinking had been an attempt to self-medicate.

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder that affects how people process their thoughts and interact with reality. As with most disorders, there’s a sizable spectrum on which people might fall. Some people with schizophrenia hallucinate, but the only time David did so was when he was detoxing. Reading David’s psychiatric records, it seems his presented itself through cognitive symptoms – specifically trouble organizing his thoughts.

Like 1 in 6 adult Americans today, David was on medication to treat his mental health. Once, in early 1980, David impulsively took 300 milligrams of Trilafon, his antipsychotic medication. Though that was 10 times more than he’d been prescribed, it wasn’t fatal. He spent about a month in the hospital, after which he continued seeing a psychiatrist, who gradually lowered his prescription to 8 milligrams a day.

The medicine seemed to help. The 1980 hospital stint was David’s last known breakdown. He got his prescription refilled monthly. After he disappeared, police searched his home and found a prescription bottle with the appropriate number of pills remaining.

Still, people with schizophrenia have higher rates of suicide than those without psychotic disorders. A study published in 2015 suggested that half of schizophrenics attempt suicide at some point in their lives, while 5% to 10% of schizophrenics will die by suicide.

That, matched with Alderucci’s perception that homicide was impossible, led investigators to conclude that David killed himself. There was no other option.

Jim Callaway, The Enquirer

When a loved one dies by suicide, it can be difficult for family members who didn’t see it coming. Even when all the evidence points to a self-inflicted death – including notes saying goodbye – some insist they would have seen red flags.

That was true with the Bocks family, but their doubts were supported by some odd developments in the months after David disappeared. In December 1984, a headline ran on the front page of The Cincinnati Enquirer: NLO Checking Possible Uranium Leak

The story began:

Unacceptably large amounts of uranium dust may have escaped from NLO’s Fernald uranium processing plant in northwest Hamilton County, NLO spokesman George Smith said Monday. If it really happened, the uranium slipped by a flawed filter and pressure monitor in a work area exhaust system for three months, Smith said. But it may not have happened, he added.

At the time, the news was curious and foreboding, but also in dispute. While it caught people’s attention, fears around the Fernald plant were, on the whole, assuaged by the company’s insistence that everything was fine.

More than three decades later, however, and the truth is easier to suss out. Things were not fine at Fernald. Not only were thousands of pounds of uranium dust being released into the air, but water wells in the area were tainted, too.

Things were not fine at Fernald. Not only were thousands of pounds of uranium dust being released into the air, but water wells in the area were tainted, too.

It would take years of investigative reporting, protracted lawsuits and scientific analysis, but the gist is this:

The U.S. government had known for decades that long-term exposure to uranium was detrimental to people’s health. They knew this because uranium miners from the 1950s had higher rates of lung and renal diseases.

“Even though our government knew that there were dangers, that was not something that folks who worked in the mines or worked in the mills in the ’40s or ’50s were notified about,” said Stephanie Malin, an assistant professor of sociology at Colorado State University. Malin has spent a chunk of her career researching the issue. She wrote a book called “The Price of Nuclear Power: Uranium Communities and Environmental Justice.”

The mysterious Fernald plant

Ben Kaufman, a former Enquirer reporter, speaks about the mysterious Fernald plant.

Amanda Rossmann and Amber Hunt, Cincinnati Enquirer

Disclosing the potential dangers might have stopped workers from doing things that, in hindsight, sound as crazy as they are dangerous – like tasting radioactive salts to decide if they would make good laboratory samples.

Reporters starting to break stories in the mid-80s about Fernald weren’t experts like Malin, however. When company and government officials insisted the plant was safe, the reporters quoted them saying so and didn’t have the expertise to push back.

But slowly, more and more experts worldwide began weighing in, and a pattern emerged: Scientists hired by the NLO or the DOE insisted everything was fine, but independent scientists – ones with no affiliation to the plant – said otherwise.

D.C. Cole was a reporter drawn to a different headline altogether.

Widow sues over NLO tissue samples

The story ran in August 1985 and described the death three months earlier of a 33-year-old man named Larry Hicks.

Hicks had worked at Fernald since 1973. On May 15, 1985, he was walking in one of the plants when a piece of equipment malfunctioned overhead, dousing him with uranium particles.

Uranium is colorless and odorless, and its effects on the human body usually take time. But Hicks began feeling ill within a day.

D.C. Cole was a self-described investigative reporter who wrote for a now-defunct weekly called Everybody’s News. Cole also wrote a book about the David Bocks case and lobbied to get it on Unsolved Mysteries. This is a screen grab from an Unsolved Mysteries episode where he was interviewed.

Courtesy of Unsolved Mysteries

On May 20, five days after the dousing, he complained of fatigue and an irregular heartbeat. He died at the hospital.

His wife, Diane Hicks, was suddenly widowed with three children. She suspected her otherwise healthy husband’s sudden death had to do with the mishap he’d had a few days earlier, but she’d need an expert to test his internal organs to help prove it.

NLO insisted the uranium dousing was a coincidence. Through hired doctors, they said Hicks died of a potassium deficiency and, therefore, his family wasn’t entitled to workers’ compensation benefits.

When Larry’s body was being prepped by a mortician for a viewing, Diane learned more upsetting news: Larry’s chest was now visibly sunken and had to be internally padded to fill out his suit.

Larry was missing bones, his liver, his kidneys and tissue from his spleen. He still had his heart.

When uranium is absorbed by the human body, the highest levels are found in the bones, liver and kidneys, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. If Diane was going to sue anybody over uranium exposure, she was missing the very organs she needed to make her case.

She changed tacks and instead sued over her husband’s missing organs. The allegations were so ghoulish, they made headlines, though Larry’s actual death had not. The unsuccessful suit and failed appeals dragged on for years.

In the early 1990s, D.C. Cole had been writing for free for local weeklies and wrote a story about the Hicks case for a now-defunct outlet called Everybody’s News.

In reporting the Hickses’ story, he learned about another death at the plant – that of David Bocks nearly a year earlier.

Cole became consumed by the story. He contacted David’s children and interviewed his coworkers. He was outspoken in his belief that Bocks was murdered and his death had been covered up by both NLO and the government.

Cole had a personal connection to Fernald, according to John Fox, then the editor of Everybody’s News. He said Cole described ailing family members who lived near the plant. Cole even wrote a first-person story about his sick mother and uncle.

Cole was a character. He wore a cowboy hat and turquoise jewelry with his biker-themed black T-shirt.

“If you met him and didn’t know he was a reporter, you’d think this guy’s just getting ready to go out to South Dakota for the bike rally out there,” Tony Bocks said.

Both Tony and Casey remember big promises: Cole was going to expose the truth, in turn taking down NLO and maybe even the government.

Amanda Rossmann, The Enquirer

Tony already believed NLO was hiding something about his father’s death, so he was open to hearing Cole’s theories. But even he found them to be “a little bit overboard.”

Cole was convinced that some other tragedies peripherally connected to the Bocks family might be part of the purported cover-up. He found it odd that David’s psychiatrist, Clifford Grulee III, died by suicide Oct. 2, 1985, before he’d been able to testify to what he told police – which was that he didn’t believe David was suicidal.

In January 1988, David’s brother Peter was killed by a hit-and-run driver while walking to work at a motel in Milford. The driver was never found.

Cole asked: If a company goes so far as to remove organs from a dead worker’s body without asking his family’s permission, is it really such a stretch to think they’d cover up the true cause of another death?

Cole died in 2016. He never took down NLO or the government, but he did score one success: He got the case featured on a segment of the TV show “Unsolved Mysteries.” The national exposure sparked a slew of tips. Most were nonsense, but a few sounded plausible.

The police file indicates Alderucci circled back to one employee who said he knew that David’s death was murder, and he even knew the killer.

“Talk to that manager. He knows a lot more than what he’s saying,” the informant said.

David’s manager at Fernald was a man named Charles Shouse. He happened to be the last man to have reportedly seen David alive.

Alderucci never circled back to interview him.

Daniel Arthur’s job was to oversee safety at the Fernald site. Hired in 1984, he worked as “lead auditor,” charged with analyzing the operation and documenting any deficiencies.

He answered to two immediate supervisors and found it odd that they ordered him not to audit several areas of the plant, but he went along.

Arthur considered his an important job. He was the only one who did it and, when he was hired, production at the plant hit the highest levels since the 1950s. But after working nearly two years as auditor, he realized he’d never talked to a single DOE official about his audits. He started to suspect that no one was even reading them.

Not only that, but he pieced together that half of the site’s routine maintenance operations were “terribly inadequate.”

“To give you an idea of the situation as it stood on January 1st, 1986, 50% – one out of two of all maintenance procedures – had not been reviewed or revised since 1960. That is 26 years,” he said during a congressional hearing in April 1987.

The first time he even saw a DOE official was after the headlines hit about dust releases. And even then, he only saw the guy on TV.

“Many of the managers would comment about it and wonder why they were making such a fuss over the release in the fall of 1984 when they felt there were certainly bigger problems and larger releases just in the past two years before that time.”

Cincinnati Enquirer

Arthur was hired one month before David Bocks died. The newly revealed safety issues at the plant had quickly overshadowed the bizarre tale of the missing pipefitter.

Arthur grew frustrated that he was flagging problems no one addressed, so he got more vocal. Then, in February 1986, he learned that Fernald had been handling plutonium shipped from sites in Hanford, Washington, and the Savannah River Plant in South Carolina – but workers didn’t know it.

Plutonium is highly radioactive. DOE regulations specified that nothing more than 10 parts per billion plutonium was to be processed without special permission. Fernald had no such permission, yet processed 7,757 parts per billion in 1982, Arthur said.

Arthur called for new procedures. Workers should not only be informed that they were dealing with plutonium, but they also should wear respirators and have regular urinalyses. His bosses told him there was no time to adopt new safety protocols. Arthur warned that if something went wrong, “We will get our ass sued off.”

Days after that warning, Arthur got a letter from his bosses accusing him of taking “excessive time off” and having a bad attitude “towards accepting more responsible assignments.”

“I read the writing on the wall, that definitely was a paper trail leading to firing me,” Arthur said. He preemptively quit in March 1986 and wrote a three-page letter explaining why. “This resignation is solely based on the Health and Safety conditions that exist at the Fernald Site,” he wrote, before outlining 12 specific concerns, among them:

It would ultimately be these issues, among many, that led to Fernald’s shuttering a few years later.

One matter that played no role in the shuttering: David’s gruesome death in a cauldron reminiscent of hell.

Patrick Reddy, Enquirer Archives

David Bocks was a stickler for the rules, his family and coworkers say. His direct manager, Charles Shouse, told police that David had complained about a worker named Earnie Gipson for sleeping on the job. Shouse caught Gipson snoozing soon after and suspended him. That suspension was underway when Bocks disappeared.

Harry Easterling told a reporter that David often warned him about dangerous spots at the plant. Those hot spots weren’t a secret, coworker Melvin Karnes said. He said his sister worked for an Ohio politician and told Karnes she’d been instructed to visit the Fernald site.

“I said, ‘Oh, hell no.’ You stay the hell out of this building, this building, this building,” Karnes said, rattling off spots he considered “hotter than firecrackers.”

Employees repeatedly were told their jobs were safe. Bosses claimed the only harm to be caused by uranium billets was dropping one on your foot. But Karnes said no one believed that. Workers wore dosimeter badges that supposedly turned red when exposed to too much radiation, but the badges were so unreliable that they became the butts of jokes.

“We used to take the dosimeter badges and lay them right on top of uranium and leave them there for damn near the whole shift,” he said. They rarely turned red.

On the rare occasion a badge did detect radiation, bosses would declare it a false positive, saying the badge was defective.

As Larry Hicks’ 1985 death showed, workers could literally be doused in uranium particles and managers would insist they were fine.

In Fernald’s final years, the site changed owners before ending production forever, but DOE remained the overseer. It set production goals and gave hefty bonuses for not reporting safety issues. Some employees claimed in lawsuits that if they did get hurt or sick, the company sent a car to their homes to take them to the plant, where they’d be kept in the infirmary long enough to say they came to work.

In short, production was king, and safety an afterthought.

“We really should not have Dracula supervising the blood bank,” U.S. Rep. Thomas Luken, D-Cincinnati, said in 1987 at the hearing regarding Daniel Arthur.

David Bocks’ children hadn’t known much about their father’s job when he disappeared. As the public scrutiny gained steam, they found themselves wondering if his death had been part of a cover-up: Maybe, they thought, their dad was killed by a coworker to stop him from blowing the whistle on Fernald.

Lisa Crawford had never heard of David Bocks when Fernald forever changed her life a few months after the disappearance.

Crawford had returned to the house she rented in Ross, across the street from the Fernald plant, in fall 1984. She learned a man had been poking around the water well in her backyard – and that she, her husband and her 7-year-old son had all been drinking water contaminated by Fernald.

“We were mad. How dare you, you know?” Crawford said.

Michael Snyder/Cincinnati Enquirer

Homeowners near Fernald had been notified that their water wells were routinely tested for contamination. Because Crawford didn’t own her house, however, she had never been forewarned of the possibility. In late 1984, she learned hers was among a few contaminated wells.

Her landlord tried to calm her fears, but Crawford asked both the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency and the Ohio Department of Health to test her well and provide second opinions.

That they provided contradictory opinions did little for her nerves. The EPA told her to find a new source of drinking water because hers was unsafe, while the health department said the water was fine. Crawford opted to follow the EPA’s advice, and she spoke to any reporter willing to hear her complaints.

When the area’s biggest employer is suddenly under fire, the community is inevitably divided. Workers who relied on Fernald for their very livelihoods got angry with Crawford for bad-mouthing their boss. She came home to death threats left on her answering machine. For months, she suspected her phone line was tapped – though she tried to handle it with humor.

“I used to pick it up (and say), ‘I gotta call my mom now, you wanna listen?’ ” she said. “We became smart alecks mostly.”

The truth about Fernald

While managers and government officials outwardly assured Fernald workers that everything was safe at the plant, internal documents show many knew that wasn’t the case.

Amanda Rossmann and Amber Hunt, Cincinnati Enquirer

At first, she was at odds with both managers and workers at Fernald. But in 1985, after the dust-release debacle, the union went on strike. Longtime workers began doubting managers’ assurances and believing naysayers like Daniel Arthur.

Gene Branham, president of the Fernald Atomic Trades & Labor Council, supported Arthur in the 1987 congressional hearing. “For the last quarter of a century that I have been actively involved, the union has been treated like poor kin, a stepchild or what have you,” he told lawmakers. “We have normally sat on the back porch and while these fellows have sat out front and eaten the roasting ears and passed the corn cobs back to us. That situation is about to change, we hope.”

Change did come, though it was clunky and incremental. In 1989, Fernald ceased production and started cleanup efforts that would last nearly 20 years. Residents and workers battled for years in court to eventually win access to a medical monitoring program.

As soon as the headlines quieted for a while, some new revelation would arise to shock the region all over again. Among them:

Despite one obstacle after another, the site eventually was cleaned well enough to become a nature preserve. Some of the most dangerous waste was shipped off-site by train and buried in Nevada. About 4.7 million tons of low-level waste, uranium-contaminated soil and building debris were buried at Fernald.

Because of that, the land will never be clean enough for homes.

A sign paying homage to the ‘First Link’ leads to the drive of the Fernald Nature Preserve. The preserve was once the home to former Cold War-era Fernald Feed Materials Production Center located in Hamilton County, Ohio.

Amanda Rossmann, The Enquirer

The police file detailing David’s death includes hundreds of pages of all sorts: handwritten scribbles on yellow legal paper; neatly typed formal reports; transcripts of interviews with Easterling and Shouse; and opinions from experts agreeing that the bone fragments found appear to be from an adult human.

Some of the notes subtly express frustration, including a two-page document titled “Processing Low-Grade Uranium.” The typed memo explains how the NUSAL vat heat-treats ingots “to alter the grain or molecular structure of the metal.” The professional-looking document closes with a strange sentence:

“It should be noted that the individual who wrote this treatise on the operation of this small section of the Fernald Plant is well versed in many technical fields, however he does not know a fucking thing about the processing of uranium.”

Though Alderucci said nothing in the case suggested murder, the police files suggest otherwise. Investigators didn’t compile a timeline of David’s last shift, but according to the myriad law enforcement documents, the undisputed parts went like this:

David met Easterling at the White Castle about 10:50 p.m. and the two drove to Fernald. They clocked in, changed from their street clothes to their work clothes, stepped through a sanitizing shower and attended a meeting, during which they were handed their assignments for the night.

David finished his jobs, and then met back up with Easterling and their boss, Shouse, for a meal break at 4 a.m. David had packed his lunch in a brand new lunchbox, which Easterling noticed and complimented. After he ate, David clocked back in at 4:46 a.m. and disappeared soon after.

But a closer reading of Easterling and Shouse’s statements highlight some odd discrepancies. Easterling said David was quiet, but no more than usual; that despite being tired, he seemed plenty upbeat, and that David was with him nonstop before his shift began.

Shouse, meanwhile, said David seemed despondent. He said that he spotted David walking toward the NUSAL vat building before he was assigned his night’s work; that David ate an extra sandwich at lunch, as though it could be his last meal, and that after the break, Shouse spent about 10 minutes trying to get David to “open up” through conversation, but his efforts failed.

With the 4:46 a.m. clock-in documented on David’s time sheet, that would have meant Shouse was talking to David around 5 a.m. – the same time the NUSAL vat readout began its spike.

According to the files, police dismissed Easterling’s version of events and embraced Shouse’s. No one else in the files – not David’s family or his friends or even his psychiatrist – believed David was suicidal. Shouse was never questioned for motive or asked to prove his whereabouts.

Another apparent lead was back-burnered. Shouse told investigators that David’s complaints led him to suspend a worker named Earnie Gipson for sleeping on the job. Gipson, who’s described as a “troublemaker” in the file, was still suspended when David disappeared. A coworker thought he saw Gipson’s motorcycle around midnight of the night in question, so police went to Gipson’s house, saw that his motorcycle was inoperable and dismissed the lead altogether. They never asked for an alibi, checked to see if he had access to other transportation or questioned him regarding motive.

Gipson did not return phone calls for this project. Shouse didn’t respond to phone messages or mailed letters, and when a reporter knocked on his door and asked to speak in person, a woman said he was sleeping. He never replied.

The unfollowed leads could, of course, be red herrings, as is true with all leads in any investigation. But to David’s children, they serve as clear contradiction to investigators’ insistence that there was no reason to even consider that David was murdered.

Tony Bocks was 17 when his father died. Like most teenagers, he was too self-absorbed to think much about his dad as a man or a worker. He knew his dad had a job at Fernald, but that mostly was because David at some point had suggested he apply there.

After his dad disappeared, Tony felt anger consume him. He’d always been a bit hot-headed, but now he was furious. He didn’t believe his father died by suicide, and his gut told him that the detectives were persuaded to call it one so they could quickly close the case.

Tony’s fury led him to drink. Unlike his father, he sometimes got violent, starting occasional fistfights.

Amanda Rossmann, The Enquirer

“One thing I’ve learned about being an alcoholic is you self-medicate your depression,” he said. “I’m not blaming my alcoholism on my dad’s death, but it played a part of it because I was a bitter person for a few years after he died. I really was.”

Tony managed to quit drinking before it ruined his marriage. He grew up, he had kids, he got a job working in a power plant. That experience reinforced his resolve.

“If I would die in that plant, I guarantee you there would be such an investigation of every second that happened during that day,” he said. “Every step, every angle that I took would’ve been on record. That didn’t seem to be the case with my dad’s death.”

Life moved on for Tony, but with an asterisk. He never felt at peace. He still keeps his dad’s Little League glove on his dashboard and wished through every one of life’s hardships that he had his dad for guidance.

As the years passed, David’s story was reduced to folklore. The tale was always told with one of three possible explanations: that David had faked his death with animal bones misidentified as human remains and run off to start a new life somewhere; that his mental health deteriorated without warning and he managed to cram himself into the vat’s slim opening; or that he was killed by a coworker who’d hoped the vat would conceal the crime.

The first possibility has faded with time. No evidence has surfaced that David is still alive, and his case has received international coverage thanks to The Enquirer’s “Accused” podcast, which reached 2 million downloads within two months.

Alderucci, now retired, recently maintained that he still “100%” believes that David killed himself. No one who knew David believes that’s the case, and several workers – as well as an Enquirer experiment involving a replica of the vat – suggest that someone David’s size would have found it difficult, if not impossible, to force himself into the vat opening.

Experiment: Would David Bocks have been able to fit in the opening of the vat?

With the help of reporter Tyler Dragon, the Accused team performs an experiment to see if David Bocks could have put himself into the opening of the salt vat.

Amanda Rossmann and Amber Hunt, Cincinnati Enquirer

To most who knew David, that leaves murder – though they don’t agree on a motive.

Maybe the reason was fairly pedestrian; maybe not.

Tony is careful to say he doesn’t think what really happened is a JFK-level conspiracy, but how could it be a coincidence that so soon after his dad disappeared in such a mind-bogglingly mysterious way that the company’s secrets are revealed?

How could a man go to work and never be seen again

David’s case is technically unsolved, despite investigators’ insistence he killed himself. With only bones to examine, the cause of death was never clear, much less the method.

Technology’s come a long way, of course, and the family would love to have the evidence reexamined, but that’s not likely to happen for a simple reason: They don’t know where it is.

The keys and metal and bits of bone were never returned to the family. While no one has been able to say for sure, the belief is the items were sealed in a drum and shipped to Nevada along with other radioactive materials.

There, the remains were buried so that the radioactivity in them cannot escape and harm others.

David’s children feel the disposal was designed to ensure the truth about his death stayed buried, too.

34946 247161My wife style of bogus body art were being quite unsafe. Mother worked with gun first, right after which they your lover snuck free of charge upon an tattoo ink ink. I was positive the fact just about every should not be epidermal, due to the tattoo ink could be attracted from the entire body. make an own temporary tattoo 367787

108983 143892It was any exhilaration discovering your site yesterday. I arrived here nowadays hunting new items. I was not necessarily frustrated. Your ideas following new approaches on this thing have been useful plus an superb assistance to personally. We appreciate you leaving out time to write out these items and then for revealing your thoughts. 260283

442740 844545Spot lets start on this write-up, I seriously believe this incredible web site requirements a lot more consideration. Ill more likely once again to read a terrific deal a lot more, several thanks that information. 524085

784463 570881Real fantastic data can be identified on internet weblog . 764531

224082 942538Hey! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with SEO? Im trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but Im not seeing very good results. If you know of any please share. Thanks! 533538

443830 798002Basically received my 1st cavity. Rather devastating. I would like a super smile. Searching a good deal much more choices. Numerous thanks for the article 255839

516425 176136It is hard to find knowledgeable individuals on this subject nevertheless you sound like you know what you are talking about! Thanks 546808

667874 401247Hey there, Can I copy this post image and implement it on my personal web log? 588782

331711 311534I undoubtedly did not realize that. Learnt something new today! Thanks for that. 148303

166144 64949Very fascinating info !Perfect just what I was seeking for! 409960

181859 584424Excellent weblog here! after reading, i decide to buy a sleeping bag ASAP 73843

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: famousreporters.com/death-lies-and-uranium-how-an-ohio-mans-mysterious-disappearance-in-1984-still-haunts-family-friends/ […]

378795 554918I recognize there is definitely an excellent deal of spam on this weblog. Do you want assist cleansing them up? I could support in between classes! 956271

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: famousreporters.com/death-lies-and-uranium-how-an-ohio-mans-mysterious-disappearance-in-1984-still-haunts-family-friends/ […]

226215 724376I was suggested this web site by my cousin. Im not positive whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my issue. Youre incredible! Thanks! 106647

556546 425814This really is genuinely fascinating, You are a really skilled blogger. Ive joined your rss feed and look forward to seeking more of your magnificent post. Also, Ive shared your web website in my social networks! 996494

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 46853 more Information on that Topic: famousreporters.com/death-lies-and-uranium-how-an-ohio-mans-mysterious-disappearance-in-1984-still-haunts-family-friends/ […]

943931 754340Sweet internet internet site , super layout, real clean and utilize pleasant. 35783